Disclaimer: This post is really long. Like really, really long. If you're gonna read the whole thing, you might want to get yourself something to drink, or perhaps a healthy snack, first. Like maybe a grapefruit? Grapefruit is pretty cool, you know.

Got it? Then read on!

Ecclesiology, for the unaware, is a word for the structure of a Church or other religious body. Now, while I'm sure you've all been hoping for an exciting examination of the structure of 1st century Persian Manicheanism in comparison to the Manichean church of the 4th century, I will instead (surprise!) be examining the ecclesiology of a more obscure religion called...(now where did I put that slip of paper?)...ahem..."Christianity." Perhaps you've heard of it?

I've been thinking about this topic quite a lot lately, and I have thought of it quite a lot more over the course of my lifetime; this post is essentially me trying to work out and fit together the various thoughts and ideas I've had on this topic in a way that halfway makes sense. It will be mostly speculation, and, while I will make references to sources where appropriate, this is not a real work of scholarship with citations and such--that, if it comes, will be another project. What this is is essentially what I've come to think and speculate after reading many of these sources and trying my best to understand and synthesize them.

Now, the Great Question of 1st century Christian ecclesiology, whether you're a Protestant, a Catholic, or a Whatever, is, essentially, "How do we get from Paul to Ignatius?"

So, looking at this development, one question should jump out at us almost immediately: Whence the Bishop? Where did this Bishop guy come from, anyway, and why is he suddenly the boss? Over the course of the years, scholars, theologians, and people in tutus have proposed any number of theories as to the origin of what is called the "monarchical episcopate" (or, put more simply, the Bishop being in charge), the most prominent of which are probably the theories of Apostolic Succession and Gradual Elevation. The first theory is that the Bishops were appointed by the Apostles as their direct successors, to, essentially, fulfill their role in the community; the second is that the role of the Bishop developed gradually over time from within the ranks of the presbyterate, with one presbyter gradually becoming more and more prominent within the body until he came to be seen as an order existing above it. We'll go over what I think of all this a bit later.

However, this is not the only major question of first-century ecclesiology. Even if we leave aside the seemingly post-Biblical role of the Bishop, there's still the question of what, exactly, is meant by the terms presbyter, episkopos, apostolos, and diakonos, officials whose roles are all very much debated in scholarly and Christian circles. This question is obviously one of great importance, as it has important implications for how we view the entire question of ministerial roles in Christianity, the priesthood of all believers, apostolic succession, etc.

Allow me to take the last question first; namely, the question of ecclesiology in the New Testament period; as we'll see, this will naturally provide us with a bridge to the earlier one.

Got it? Then read on!

Ecclesiology, for the unaware, is a word for the structure of a Church or other religious body. Now, while I'm sure you've all been hoping for an exciting examination of the structure of 1st century Persian Manicheanism in comparison to the Manichean church of the 4th century, I will instead (surprise!) be examining the ecclesiology of a more obscure religion called...(now where did I put that slip of paper?)...ahem..."Christianity." Perhaps you've heard of it?

Apparently, Christianity is a pretty big deal. Who knew?

Now, the Great Question of 1st century Christian ecclesiology, whether you're a Protestant, a Catholic, or a Whatever, is, essentially, "How do we get from Paul to Ignatius?"

St. Paul thinks

That is, the Apostle Paul's writings (which you can find in the New Testament) are pretty much THE source we have as to the day-to-day workings of the various Christian churches circa 50-60 AD, and from them, people have developed all kinds of theories about how things worked; these are supplemented by information we get from the Didache (a 1st century catechitical text) and the other books of the New Testament. While I'll go over it in more detail later, the long and the short of it is that the Pauline letters show us a church structure with basically two levels of organization: the local one, composed of officials known indifferently as "presbyters" (elders) and "episkopoi" (overseers) and inferior officials known as deacons; and the super-local one, composed of inferior officials known as "prophets" and "teachers," and superior officials known as "Apostles."

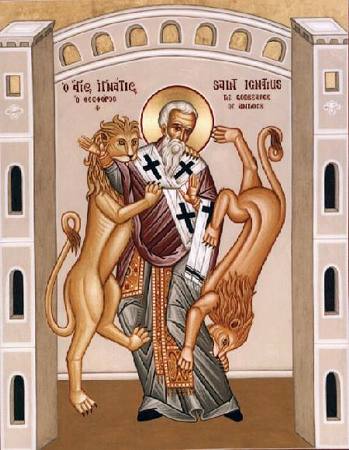

St. Ignatius plays with lions

However, if we jump about 50 years forward to the years at the very beginning of the 2nd century, shortly after the death of the last Apostle, we have seemingly a completely changed ecclesiastical structure, universal throughout the entire Church. One of our earliest and best sources for the structure of the Church at this time is St. Ignatius of Antioch, a Bishop (hey, what's that? you may ask. Well, that's kinda the point) of Antioch in Asia Minor, who at around the turn of the century was forcibly removed from his flock and taken to Rome to be fed to the lions. Along the way to his destination, Ignatius wrote a series of letters to various prominent churches in the Roman world, presenting his final lessons on doctrine and practice while preparing to meet his Lord. In this letter, Ignatius emphasizes one single thing over and over and over and over again, with as much emphasis as it is possible to give anything: the absolute centrality and necessity of communion with "the Bishop," the singular official presiding over almost every Church throughout the world. The Bishop, Ignatius makes clear, is simply the fulcrum point on which the Church itself hangs; those who are in communion with the Bishop and obey his authority are within the visible bounds of the universal Church, and those who are not are heretics and schismatics. And lest you think that this was simply Ignatius day-dreaming a little bit on the road, his letters (and the fact that they were preserved by the communities he sent them to) make it very clear that all the Churches he writes to already possessed just such a Bishop, who already made all these claims and was obeyed by the vast majority of the faithful. Besides this, in every place to which Ignatius writes, there are also the two other groups of officials which we have already encountered, the presbyters and the deacons, whose role (according to Ignatius) is to assist the Bishop in carrying out the work of the Gospel. Apostles, as we might expect, are looked back on as part of a past age.So, looking at this development, one question should jump out at us almost immediately: Whence the Bishop? Where did this Bishop guy come from, anyway, and why is he suddenly the boss? Over the course of the years, scholars, theologians, and people in tutus have proposed any number of theories as to the origin of what is called the "monarchical episcopate" (or, put more simply, the Bishop being in charge), the most prominent of which are probably the theories of Apostolic Succession and Gradual Elevation. The first theory is that the Bishops were appointed by the Apostles as their direct successors, to, essentially, fulfill their role in the community; the second is that the role of the Bishop developed gradually over time from within the ranks of the presbyterate, with one presbyter gradually becoming more and more prominent within the body until he came to be seen as an order existing above it. We'll go over what I think of all this a bit later.

However, this is not the only major question of first-century ecclesiology. Even if we leave aside the seemingly post-Biblical role of the Bishop, there's still the question of what, exactly, is meant by the terms presbyter, episkopos, apostolos, and diakonos, officials whose roles are all very much debated in scholarly and Christian circles. This question is obviously one of great importance, as it has important implications for how we view the entire question of ministerial roles in Christianity, the priesthood of all believers, apostolic succession, etc.

Allow me to take the last question first; namely, the question of ecclesiology in the New Testament period; as we'll see, this will naturally provide us with a bridge to the earlier one.

The Undisputed Deacon

To start with, we'll begin with the easiest matter of all; the diaconate, whose role in early Christian communities is fairly simple, has never been seriously disputed, has never been seriously altered, and is the only one of these offices (save that of Apostle) to actually have its origin and function provided for us in the Scriptures. Diakonos means, essentially, a servant, or, more technically, someone who supplies something for someone else or provides for their needs. In an uncharacteristic display of kindness towards future scholars, the Acts of the Apostles actually provides both an origin story (!) and a function (!) for the diaconate--namely, that there arose dispute about the distribution of resources and charitable funds in the early Christian community, and the Apostles, not wanting all their time taken up by material charitable work, appointed seven men with the task of providing for (diakonein) the poor and widows within the community. According to Acts, these men were designated for their position by a "laying on of hands" by the Apostles, an act which we will examine in a little more detail in a moment. Nevertheless, this clearly indicates for the New Testament period at least an officially designated office with the task of caring for the poor and distributing charitable donations and such--and this is essentially the same office as we see fifty years later with Ignatius, and throughout Church history. The only real controversy about the diaconate, such as it is, is the question of female deacons, and whether or not they were really ordained in the same way as ordinary deacons--and that doesn't really fall within the purview of this essay/blog post/whatever-the-kark-this-is.

Ho Presbyter?

However, then we get to the big scrap-up of all scrap-ups: the office of "ho presbyter," otherwise known as the priest, the elder, the pastor, the preacher, the presbyter, the minister, the worship leader, and a hundred other things. Even more than the other offices we'll talk about, the poor presbyter gets dragged back and forth across the pages of the Bible, morphing at a moment's notice from a sacerdotal Priest to a Congregationalist Preacher to a travelling minister of the Word to a temporary delegate of the community to a praise-band leader to the lead singer of a Christian rock band to Waru-knows-what-else without even being able to get a word in edgewise.

Ho Presbyter?

See, the problem is that, unlike with the diaconate, no one through all the length and breadth of the New Testament ever goes to the trouble of explaining to us just what a presbyter is, exactly, or what in the name of Colney Hatch he's supposed to be doing. Apostles write to him, ordain him, even call themselves one--but that's hardly enough to draw up a job description. If that's not bad enough, even the title itself comes off, at least for an English speaker, as profoundly disappointing, since "older man" is hardly an inspiring kind of thing to call one's spiritual leader. A lot of the history of the modern Protestant Church has been trying to find something a bit more exciting to call the guy--while Catholics and Anglicans, with typical good sense, just skipped the whole exercise and contracted the Greek word into "priest." The fact that he also frequently gets called "ho episkopos" hardly helps matters; one certainly doesn't want to go around calling one's spiritual leader "overseer" or "supervisor."

In any event, neither of these titles are, on the face of it, particularly descriptive. While the idea of an old man may, for us moderns, not mean much of anything, for a first century Greco-Roman it would convey at least the idea of legitimate authority, wisdom, and power, since age was seen in Roman, Greek, and Jewish society as essentially equivalent to authority. Likewise, "overseer" conveys at the very least "authority figure." However, if all we have to go on are the words themselves, and the information given to us about them in Scripture, we frankly don't have very much, as might be indicated by the various and ever-multiplying ecclesiastical structures possessed by "Sola Scriptura" churches.

Ho Presbyter?

However, perhaps that's not all we have to go on, after all. As we should know by now, the most important key to understanding Scriptural texts is quite often not the texts themselves, but the context, especially the larger contexts of Second Temple Judaism and Greco-Roman society. So, we might ask, where else in these societies (both with significant Greek-speaking populations) do we see the word presbyter come up? Well, there are any number of sources for the Jewish context of the first century, many of them from much later times, and not many of them being particularly helpful for our cause--but as a matter of a fact, one of our best and most contemporary sources for first-century Jewish society happens to be...the New Testament itself.

Shocker, I know. Anyway, in actuality this post was partially inspired by my noticing that, in actuality of fact, the word presbyter appears rather frequently in the Synoptic Gospels and Acts in a purely non-Christian, Jewish context. In fact, the word "presbyter" occurs a full 13 times in such a context in the Gospel of Matthew alone-- Matthew being the most Jewish of all the Gospels, self-consciously written to a solely Jewish audience familiar with the details of Jewish customs and culture. However, in this, Matthew is far from unique; as a matter of a fact, the word is used in Luke, Mark, and Acts in the same context, to denote seemingly the exact same group of people. Now, you may ask, what precisely is this context which I consider so important? What do the Synoptic writers see presbyters as being in the context of Jewish society?

By way of answer, let me quote a representative passage from the Gospel of Matthew:

"From that time forth Jesus began to show unto his disciples that he must go unto Jerusalem, and suffer many things from the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and be raised again the third day." (Mt. 16:21)

And another:

"Now the chief priests, and elders, and all the Sanhedrin, sought false witness against Jesus, to put him to death." (Mt. 26:59)

And one from Acts!

"And they stirred up the people, and the elders, and the scribes, and came upon him, and caught him, and brought him to the Sanhedrin." (Acts 6: 12)

Essentially (with one exception that I'll talk about in a second), this is the only way the term presbyter is used in the entire New Testament in a non-Christian context. The meaning, as should be clear from the above, is more or less a designated member of the elite of Jerusalem, or, more specifically, a designated member of the Sanhedrin of Jerusalem. In fact, as has been pointed out by scholars before, it is almost certain that, in all these passages, presbyter (or "presbyter of the people") is used to mean no more or less than "member of the Jerusalem Sanhedrin": the word presbyter in this context always appears together with at least one of the two groups that made up the Sanhedrin--the chief priests and the scribes--and almost always, as with the above, in the explicit context of a meeting or action of the Sanhedrin.

"But wait!" you may ask. "Just what is a Sanhedrin, anyway?" I'm glad you asked! For the origin of the Sanhedrin, we're going to take a brief detour to the Old Testament, and a lovely moment therein:

"And the Lord said to Moses: Gather unto me seventy men of the elders of Israel, whom you know to be elders and teachers of the people: and you shall bring them to the door of the tabernacle of the covenant, and shall make them stand there with you, that I may come down and speak with you: and I will take of your spirit, and will give to them, that they may bear with you the burden of the people, and you may not be burdened alone. [...] And the Lord came down in a cloud, and spoke to him, taking away of the spirit that was in Moses, and giving to the seventy men. And when the spirit had rested on them they prophesied, nor did they cease afterwards." (Numbers 11: 16-17)

Another grouping of seventy "elders" had earlier been permitted to go up on the mountain of Sinai with Moses, and there behold the glory of God himself. And if you've been paying attention, you'll probably guess that the word used for "elder" in the Greek Septuagint version of the Old Testament (the version most commonly quoted by the Evangelists) is...wait for it...presbyter!

Moses wonders: "Just what is a presbyter, anyway?"

In actuality of fact, this council of seventy elders probably isn't the same thing as the Sanhedrin at all; however, at the time of Christ and for centuries before, the Sanhedrin's existence was always explained and supported with the use of these passages--so it is quite natural that the Gospel accounts (and most likely many Greek-speaking Jews of that time) would refer to members of the Sanhedrin by the name of "presbyter."

The Sanhedrin was, essentially, a Council of seventy-one men (seventy elders plus the president) drawn both from the ranks of the priests living in Jerusalem, and also from the ranks of the scribes, learned interpreters and teachers of the Law, with some overlap between the two classes. The Sanhedrin was at the time of Christ the chief judicial body of Jewish society, the "House of Judgment," as it was known, and it had full authority over every Jew in Israel to pronounce judgment, hear appeals, bind and loose sentences, and see that they were carried out. In addition, there seem to have been smaller, subordinate "Sanhedrins" in every city within Palestine itself, each consisting of twenty-three judges from whose judgments appeal could be made to the Great Sanhedrin in Jerusalem.

This latter fact would explain the only other use of "presbyter" in the New Testament, namely Luke's mention of "elders of the Jews" (Luke 7) being sent to Jesus on behalf of a Roman centurion in Capernaum--most likely, these were members of the Sanhedrin in that town.

In any event, though, other than this one mention, the Gospels always use the word elder to mean a member of the Jerusalem Sanhedrin, the chief judicial body of Israeli society at the time of Christ, a body whose president was none other than the High Priest himself. Members of this council were designated from the ranks of the priests and scribes, and ordained for their role by a solemn laying on of hands (sound familiar?).

These presbyters, even when not in council, would also have individually played the role of leaders and rulers within the Jewish communities, authoritatively interpreting and teaching the Law, resolving disputes, and (for the priests) sacrificing in the Temple when their lot came up.

Sooooo...to sum up, based on what we've seen, for at least the writers of the Gospels, and most likely (based on this evidence) for many first-century Jews, the word presbyter would have meant, first and foremost, a member of a Sanhedrin appointed by laying on of hands and tasked with the judicial rule of the community and, indeed, of all Israel. It is my argument that this position was, essentially, the primary referent in 1st century Christianity for the office of presbyter; indeed, Acts moves in short order from dealing with the "presbyters" of the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem to dealing with "presbyters" of incipient Christian communities, with little to indicate a profound difference between the two.

To bolster my argument, let me just mention that, in the letters of St. Ignatius of Antioch that I've already mentioned, the presbyterate is specifically named (and distinguished from the Bishop and deacons) as "the Sanhedrin of God." I rest my case, your honor.

"Alright, alright!" you may be saying; "So the office of elder is probably based on the Jewish Sanhedrin! So what?" Well, if we take the Sanhedrin as our primary contextual referent for the office of presbyter in the New Testament, this has a lot of important implications. To start with, the use of the term "presbyter" in a Jewish context would immediately and most strongly have a judicial meaning--naming the leaders of your community presbyters might be an indication that they played in some sense the role of judges within that community, meting out penalties and absolutions as necessary. The use of the term would also have had strong overtones of both the sacrificial priesthood and the scribal position of authorized interpreter and teacher of the Scriptures, since the ranks of the Jerusalem Sanhedrin were drawn exclusively from these two groups, and the ranks of the other Sanhedrins would have been largely drawn from them as well (the vast majority of priests lived outside of Jerusalem when it was not their lot to sacrifice and played the role of community leaders and teachers along with the Rabbis). It also implies a strong overtone of a conciliar or at least collegial method of governance, in which the presbyters acted together in carrying out their duties and ruling the community. As a matter of a fact, this conciliar nature of the presbyterate, while it survives very little today, has been at least more prominent throughout history, such gatherings of clergymen being frequently decisive in Church governance and in the election of Bishops--the most prominent place it survives today would be the College of Cardinals in Rome, which in its origin and name is nothing other than the conciliar body of the most important ("Cardinal") presbyters of the city of Rome, the holders of the most ancient pastorates, tasked as a body with gathering together in Council to elect the Bishop of Rome, and assisting him collectively with his duties.

"Okay, okay!" you may be saying. "Stop blabbing on about the Pope and Cardinals! What does all this have to do with first-century ecclesiology?!" I concede your point-- but hopefully, my main contentions at this point should be fairly clear. Essentially, I am arguing that the office of "presbyter" in the 1st century Church was almost certainly a designated office loosely patterned after that of a member of a Sanhedrin in 1st century Judaism, who like his namesake possessed judicial, teaching, and priestly powers, and who assembled together with his fellows in Council for the governance of the local Christian community. Otherwise, we have only to look to the New Testament to fill in the gaps. According to Acts, presbyters were ordained (like the deacons earlier) directly by Apostles (Acts 14:22), and according to the Pastoral Epistles (which, whatever you may think of their authenticity--and I personally have little doubt that they are genuine--are accepted by almost all as evidence of the state of ecclesiology at least in the late first century) this was accomplished, as with the Sanhedrin, by an imposition of hands (1 Timothy 4:14).

So! The presbyter! Isn't he delightful?!

The Delightful Presbyter

However, all this raises a question that brings us rapidly to our next phase of controversy: namely, if the Sanhedrin is so key to the identity of the presbyter, then why has so little of the conciliar nature of the presbyterate survived? To hopefully answer that question, we'll need to look at the next class of people mentioned: the people who, according to Acts, are those guys who happen to have ordained both the deacons and the presbyters...yes, you've guessed it, Marge: THE APOSTLES!

Congratulations, Marge! For picking the right ecclesiastical office, you've just won a free, all-expenses-paid tour of the Cardinal Basilicas of Rome, as well as a year's supply of our home game, "Guess that First Century Ecclesiastical Office: The Game with only Four Answers!" Next up, we'll have...

(Ahem) Sorry 'bout that. Anyway, we've now reached the Question of the Apostles. "Wait a second!" you might be saying: "What question of the Apostles? There's nothing simpler than the Apostles! You know, twelve guys appointed by Christ to spread the Gospel, write letters, smack down heretics, and then get horribly martyred! What else is there?" Well, as it turns out, somewhat more than you might imagine. If we actually look at the content of the New Testament, of how the Apostles existed within the first century Church, how they interacted with the other elements we've discussed, then we're suddenly looking at something almost completely unprecedented. Here, we have the Apostles creating out of nowhere an entire class of officials dedicated to the work of the poor--there, we have the Apostles appointing out of nowhere entire colleges of presbyters in almost every city in the Roman world and tasking them with government--and then, we have Peter, Paul, and John, Apostles, writing alone to those churches and completely overriding the authority of the presbyters, giving them authoritative teaching to be held and taught by all the faithful, commanding them to excommunicate members of their community or receive them back, sending personal representatives to effectively reorganize and alter entire communities, and the like. Note carefully that these these commands and actions are justified in these letters (to the extent they're justified at all) solely by the Apostolic status of the sender--the status of these letters as Scripture is neither here nor there for the first-century Church, since Paul could hardly write an angry letter to a hostile Corinthian community and justify his commands with a "Hey guys, this letter is totally Sacred Scripture inspired by God, so do what it says," nor could he rely on any kind of warm, fuzzy feelings in the hearts of the people he was angrily denouncing.

The Apostle at work

In short, then, we see a system where, while the presbyterate may constitute the local authority of the Church, the super-local authority of the Apostles possesses the authority not only to set up the presbyterate and ordain its members, but also to completely override any local body and give them doctrinal, moral, and disciplinary commands in the name of God himself. In this system, the presbyterate, whose model the Sanhedrin was the central judicial authority of Judaism, is revealed as an immensely secondary reality, and an immensely secondary authority. In actuality of fact, however much the presbyters may be doing, the Apostles are the ones running the show on just about every level imaginable. We can see this also, perhaps, in the other word used of the presbyters; namely, that of episkopos, overseers or supervisors, a word that often has the meaning of an inspector or someone appointed to watch someone else's goods or property. In this sense, this title of episkopos would also serve to underline the fact that the Christian presbyterate exists to manage and oversee things on behalf of the Apostles, not as a supreme authority in their own right. Likewise, this secondary nature of the presbyterate should help to explain at least somewhat why the conciliar role of the presbyterate has been neglected over the centuries: this functioning as a supreme judicial council could really only exist, as it existed for the presbyterate's Jewish counterpart, to govern a community in the absence of immediate higher authorities. However, when the Apostles themselves were present in the community with supreme authority to govern and override all decisions of this council, we would hardly expect it to function in the same way--in fact, we might expect it rather to have a much reduced function, and for the presbyterate to largely play the role of helpers of the Apostles in their work of supreme governance-- the role, in other words, the individual Jewish priest-presbyter would have played in his local community, teaching the Law and sacrificing when his lot came up.

The Apostle at work

However, this raises an important question; didn't the Apostles die? And weren't there only twelve of them anyway? How, exactly, could the Apostolic authority be so common, and how could it continue after the death of the Apostles? You're not going to bring up that Bishop guy again, are you?

No, no, don't worry all you non-Anglican Protestants; we haven't gotten to the Bishop quite yet. Instead, we're going to ask a nice, musical question that I'm sure you've all been waiting for: just what is an Apostle, anyway?

Before you protest, let me point you to a few verses that might help illustrate what I mean..."But I have thought it necessary to send to you Epaphroditus, my brother and fellow labourer and fellow soldier, but your apostle." (Phillippians 2:25)

And another: "Which, when the apostles Barnabas and Paul had heard, rending their clothes, they leaped out among the people, crying..." (Acts 14: 14)

"Wait!" you might ask. "Howbeit is it that Barnabas and Epaphroditus can be called apostles?! They are not of the Twelve!" Well, I'm glad you asked! I'm also glad that you said "howbeit," though I'll acknowledge that's a little off-topic.

Anyway, this isn't that big of a deal, but it does help to highlight a few things that are going to be very important in a moment. First of all, it highlights the actual meaning of the word Apostle: namely, what it really means is not, as you might expect, "one of Twelve dudes appointed by Christ to preach the Gospel, write letters, and then die horribly," but rather "a delegate"--that is, someone appointed by someone else to carry out a task on their behalf, someone delegated authority to carry out that task, and thus someone with the ability to act to an extent on behalf of the delegator. Now, this isn't necessarily that common of a word, so there's not too much room for confusion...but the point is, the word Apostle is a little broader than you might think. The 12+Paul Apostles, if you'll notice, usually identify themselves not just as an "apostle," but as an "apostle of God," an "apostle of Christ," or (more explicitly) "an apostle, not of men, neither by man, but by Jesus Christ and God the Father" (Galatians 1:1)--what all this means, of course, is that they are specifically delegates of Christ, and of God, not delegates of men. These Apostles are unique in that they receive their delegated authority directly from God, and thus possess (to an extent) the ability to act on behalf of God himself, as his unique representatives.

That being said, let's back up and take a look at those two quotes we saw a moment ago. In both of the above instances, the two people identified as apostles (we'll use apostles with a little a to denote this kind of apostleship) have a few things in common: namely, they're both people strongly associated with Apostles (big A for the Jesus-12 type), and in the former case, the person involved is in fact being sent by an Apostle (Paul) to act directly in his stead, to act, apparently, as a "proxy apostle" or "apostolic delegate" for the community...or, in other words, an apostle of an Apostle. How interesting!

In fact, if we look more closely, we'll see these types of apostles popping up more and more...in fact, at least, if not in name. To start with, there are our good friends Barnabas, Timothy, and Sylvanus, who seem to share in Paul's Apostolic authority enough to be listed as co-authors of many of his letters, and who almost always travel around with him and share seemingly directly in his ministry to the Gentiles and his Apostolic authority, being called Paul's "fellow-workers," his "son," and the like, and sent to Churches either in lieu of his own presence or in addition to it. In addition, Barnabas even seems to possess such power on a more permanent and less constrained basis, going on missionary journeys of his own, choosing his own companions, and the like, without much in the way of direct oversight by an Apostle.

However, the absolute best information we have on this kind of apostle, which both confirms and supplements what we've already seen, is found in the Pastoral Epistles, whose authenticity, as I've said, is somewhat more controversial in modern scholarship. Nevertheless, even if we suppose, for the sake of argument, that these Epistles are in fact not written by Paul, they would still serve to testify to the organization of the Church only a few decades later, and also to testify to how the organization of Paul's Church was viewed at that time; and in any event, the evidence we get from them is at best only a supplement to what we have already discovered. Nevertheless, for myself I do not consider the arguments against the authenticity of the Pastorals to be at all convincing or even particularly difficult, and so I will be from hereon proceeding from the assumption that they are genuine. Thou art warned.

St. Timothy the apostle

Now, the Pastoral Epistles provide us with a very good, very nice look at how exactly the process of Apostolic delegation worked, and what exactly such a delegate was supposed to do. These epistles are written by Paul to Timothy and Titus, respectively, both of whom had been frequent companions with Paul on his journeys and participators in his ministry. Now, however, they are separated from Paul, and have been sent by Paul as delegates to certain cities and regions to act in his stead and exercise his authority. There, they seemingly possess supreme, apostolic power over the local church and the local presbyters, possessing the authority to ordain presbyters/episkopoi (Titus 1:5, et al), and also the authority to judge and publicly condemn them (1 Timothy 5:19-20), as well as the authority to authoritatively teach and proclaim the Gospel to all (2 Timothy 4:2). In other words, in a very real way, these apostolic delegates are authorized to act in the stead of the Apostles themselves. More than this, however, these men as specially charged with faithfully keeping the Apostolic teaching, obeying its dictates, and passing it on in turn to others. This comes across most clearly in 2 Timothy, a letter written shortly prior to Paul's own death to a seemingly absent Timothy currently fulfilling his apostolic commission in an unknown location. In this letter, Paul greets the absent Timothy and calls upon him to continue his apostolic ministry, even after Paul's own death, (2 Timothy 4:1-5) and also to faithfully keep, teach, and pass on his and the other Apostles' teaching to others, in perpetuity: "And the things which you have heard of me by many witnesses, the same commend to faithful men who shall be fit to teach others also." (2:2) Indeed, even at this time, Paul is still perhaps sending out others to various places as delegates (4:12), delegates whose mission will almost certainly outlive him.

The point of all of this, put simply, is that the Apostolic power, even during the lifetime of the Apostles was far from a completely unique or completely extraordinary thing, that it was indeed both shareable and frequently shared with various other persons to various degrees, who already in the lifetime of the Apostles frequently and perhaps even habitually exercised Apostolic power in the absence of the Apostles themselves. Thus, the local churches, normally ruled by presbyters, would not have been at all unused to having apostolic authority in contact with them, even though the Apostles themselves, being only at their greatest extent thirteen men--and men extraordinarily prone to being martyred at that--could not possibly have a significant presence in such a massive and geographically dispersed Church.

St. Titus the apostle

Indeed, even the Didache (a Christian instructional document usually dated to the mid first century) seems to have far more of this situation in mind, since its main mention of "apostles" is as at least fairly common, temporary messengers who are to be received "as the Lord"--namely, as possessing absolutely supreme authority over the local church--but rejected if they stay more than two days or try to profit from their status materially. This doesn't exactly match up with the information in Paul, where these apostolic delegates have considerably more latitude--but in Paul, the delegates always come with an explicit, verifying correspondence from the Apostle Paul himself giving their mission and personally authorizing their continuing presence, and it may be that the Didache's instructions are for the probably more common, less extraordinary situations where such was absent or unnecessary. Of course, it could also be the case (as some have argued) that the Didache reflects somewhat of a push-back by local presbyteral bodies against what they perceived to be undue meddling in their affairs by apostolic authority. If so, though, the fact that even such a pushback does not dare to dispute the absolute supremacy of such apostolic delegates and the necessity of treating them and obeying them as though they were the Lord himself, is quite significant.

Also, viewed in this light, Paul's defenses of his Apostolic authority begin to make somewhat more sense. Especially, Paul's frequent and constant emphasis (esp. in Galatians) that he is "an apostle, not of men, neither by man, but by Jesus Christ and God the Father" (Galatians 1:1), that his Apostleship owes nothing to the other Apostles, that he saw Christ himself, that he received his commission from Christ himself and not the other Apostles, begins to make a bit more sense if we see Paul as trying to distinguish himself from a class of persons who were in some sense sharers of apostolic authority, but only inasmuch as they had received a commission from the Apostles to carry out some task or mission on their behalf. In doing so, Paul is not trying to distinguish himself from the other Apostles, or set himself up in opposition to them, or even deny their importance--what he is trying to do is to stress that he is one of them, a direct delegate of God, able, like them and in conjunction with them, to promulgate the teaching of God himself and act in his stead, rather than a delegate of theirs or any other man's.

If we accept all this, then suddenly the distance between Paul and Ignatius is significantly diminished. Given the existence of this class of people possessing delegated Apostolic power, and given that many of them seem to have been appointed by the Apostles to oversee specific areas for significant periods of time, and given that many of them seem to have been used to exercising their authority for long periods of time without direct oversight from the Twelve Apostles, and given also that, if 2 Timothy is believed, many of them were specifically intended by the Apostles to continue their apostolic ministry after the death of the Apostles themselves and pass it on in turn to others, then we are now about 90% of the way to the ecclesiastical structure of St Ignatius.

Plus, both Paul and Ignatius died horribly. That's got to count for something, right?

Basically-- and if I haven't made this clear yet, my apologies--it is my contention that the monarchical Bishop found in Ignatius is nothing other than the direct successor of this class of apostles of Apostles found in Paul's day, continuing to exercise supreme Apostolic authority in the Church even after the death of the Apostles themselves. As St. Ignatius, writing 40 to 50 years after St. Paul's death, emphasizes, the Bishop is precisely the one who has been entrusted apostolic authority and the apostolic doctrines by the Apostles themselves, who has the sole authority to authorize, appoint, and depose presbyters and deacons, and, in short, who is constitutive of the Church of his day in almost the same way as the Apostles were of the first-century Church.

Thus, you may say that I am firmly a subscriber to the theory of Apostolic Succession, as against that of Gradual Elevation. Besides the support I have just given--and I think that that is substantial enough--there is also the matter of the alternative theory. Essentially, it is, in my judgment and that of many others, simply a historical impossibility and absurdity that such a massive, ground-breaking, earth-shattering change in the most basic structure and concept of the Church as the Gradual Elevation theory proposes could have occurred simultaneously in dozens of separated, persecuted, heavily tradition-based communities without so much as a squeak of protest or controversy anywhere--and the absurdity is only increased when we see the "new" structure, at the very beginning of its existence, already defining itself everywhere as the most important, constitutive element of the Church and justifying its own existence by appeal to nothing other than the universally-known, universally-acknowledged Apostolic tradition and the doctrine of Apostolic Succession. Furthermore, the idea that such a structure as the presbyterate--based, as I have said, on a conciliar Sanhedrin with a weak presidency possessed of few actual powers and not even permanently attached to an office--would naturally--not to mention gradually, in the course of less than fifty years!--give rise to one member declaring himself as a completely separate office above the presbyterate, constitutive of its very existence to such an extent that it could claim no legitimacy without him, able to do what he wished with it, and have the presbyterate completely accept his claims and approve them as the ancient teaching of the Apostles--and for all this to happen simultaneously in almost every significant church in the Mediterranean--is such an absurdity that it almost embarrasses me to write it. If the Presbyterate, as it existed in the form of the Jewish Sanhedrin, had been from the beginning all there was, or at least all that survived the death of the Apostles, then, to take the example of the Jewish Sanhedrin, the presbyterate would have remained simply a loose council of elders ruling various communities without trouble, and even the most particularly brilliant, powerful, and universally-admired presbyter would have simply ended up forming some kind of family prominence or oligarchy within the Sanhedrin itself, just as the family of Annas and the wealthiest and most prominent priests formed an oligarchical party within the Sanhedrin at the time of Christ, or just as Hillel, the most famous, brilliant, and successful Rabbi of the first-century-BC, universally admired, approved, and praised, and the founder of a Rabbinical school that continues even to this day, only managed to get the presidency of the Sanhedrin transferred to him and his descendants for a few generations. Only after the most Earth-shaking controversy and upheaval--akin to the transformation from Roman Republic to Empire-- would a situation have ever resulted where even one local Church would have been transformed in such a way, with one presbyter the unchallenged ruler of the Church, holder of a separate office, and all others merely his assistants.

The theory of Apostolic Succession, then, would seem to hold the field, as much now as it did for the early Church. There are certainly other ways of framing it than I have done, and I do not at all claim that my understanding of all these issues is necessarily correct or even universal among holders of the Apostolic Succession theory--indeed, quite a bit of it is very speculative-- but nevertheless, there it is. The Bishop is, in my estimation, the immediate descendant and virtual equivalent of the Apostolic delegate, the successor of the Apostles, appointed by the Apostles before their death to act in their stead and continue their ministry within the Church. These delegates, left in place throughout the world after the death of the Apostles Peter and Paul, continued on as they had before, preaching, teaching, judging, and ministering, and over the next fifty years gradually appointed other such apostles to oversee other cities and to succeed them in ministering to their own, until we get the Church as it existed in the time of Ignatius, with almost every city possessing its own Bishop to minister to them and govern them in the Faith.

Apostolic Succession smacks down Arius

Soooooooo...that, in short, is what I think of first-century ecclesiology. However, there is one, teensy-weensy little issue that I want to touch on before closing.

Namely, if you notice, while the Apostolic delegates I've discussed are sharers in the Apostolic power and authority, and exercise it in respect to their flock, there is some important differences between them and the Apostles. Most notably, there is the fact all these apostolic delegates--as well as the Bishops who succeeded them-- possessed a limited apostolic authority, limited, essentially, by the nature of their mission and by its limitations in time, area, and the like. Thus, the Bishop is limited in his Apostolic authority to the area in which he has been granted the office of Bishop, and cannot exercise that authority, for the most part, outside of it. However, obviously the Apostles Peter and Paul were not at all limited by such things, possessing, as Apostles, the ability to exercise their supreme authority anywhere in the world--and more than this, to oversee the whole range of Apostolic delegates throughout the world and see that they carried out their missions faithfully and in accord with the Apostolic teaching.

Thus, while Bishops possess full Apostolic power, they do so in a geographically limited fashion. However, might it be that this universal, overseeing Apostolic power, exercised in a special way by Peter and Paul in their letters and appointments, also survived in some way, or was passed on in some way? Might there not be some authority remaining able to authoritatively intervene, as Peter and Paul had done, in the affairs of a Church anywhere in the world, give commands to its flock, send delegates to it to set things in order, and the like?

A short time after the death of Peter and Paul as martyrs in Rome, an insurrection took place in the Church of Corinth, with certain presbyters being deposed, certain others claiming to succeed them, and the whole Church plunged into confusion and bitter infighting. While still alive, Paul had dealt with similar problems in the Corinthian Church by sending a series of doctrinal letters to them, commanding them by his Apostolic authority to cease their dissensions, and sending to them his delegates to set things in order. However, Paul was now dead, as was Peter, as was practically every Apostle except, perhaps, the aged John living in retirement in Asia Minor. Given this situation, and given the fact that few, if any apostolic delegates would remain with the power to act outside of their own bounds, we might expect the situation to languish and grow worse quickly, with little hope of extrication, or else for the Apostle John to finally rouse himself out of his retirement enough to send a strongly-worded letter and set things in order.

You know he's gonna hit you with that crook...

In the end, though, neither of these things happened. The Church of Rome, where Peter and Paul had only recently been martyred, sent a letter--written, according to universal tradition, by Clement the Bishop of Rome--to the Church of Corinth, a letter written almost as if Peter and Paul had never died. In this letter, Clement admonished the Corinthians in the strongest terms for their disobedience, their dissension, and their love of strife, and exhorted them concerning the necessity of order and obedience in the Church, quoting profusely from the letters of Paul and Peter, commending to the Corinthians' attention the recent martyrdom of Peter and Paul in Rome, and finally commanding them in the strongest tone of Apostolic authority to obey his exhortations:

"But if any man should be disobedient to the words spoken by God through us, let them understand that they will entangle themselves in no slight transgression and danger; but we shall be guiltless of this sin."

Having finished his exhortation, he promises to send delegates to the Corinthians to set things in order, just as Peter or Paul might have done.

Indeed, reading this letter, we might begin to suspect that a continuation of Peter and Paul's authority might have existed after all...

As to the implication of that, I'll leave it for you to figure out on your own.

The Apostle at work

Well, I'm done.

If you've made it all the way through this massive, stonking tome of speculation and obfuscation, you have my respect and gratitude. To make up for what you had to endure to get this far, I've included a music video featuring Elijah Wood, a beard, and some really groovy outfits.

Also, go eat a cookie. You deserve it.

Brief Addendum: I didn't touch at all on the office of "prophet" that I briefly mentioned above. Honestly, there's not all that much to say; prophets seem to have been teachers and preachers inspired directly by the Holy Spirit rather than appointed by the Apostles, but still very much under the Apostle's doctrinal and disciplinary authority, who served local communities with their gift or else traveled around dispensing wisdom. They seem to have largely vanished after the death of the Apostles, though we get some fake ones stirring up heresy later, as well as some ones generally regarded as genuine.

Finally, a disclaimer, in the words of Thomas Aquinas himself:

I do not wish to be obstinate in my opinions. If I have written anything erroneous concerning this sacrament or other matters, I submit all to the judgment and correction of the Holy Roman Church.

No comments:

Post a Comment