Disclaimer: This post is really long. Like really, really long. If you're gonna read the whole thing, you might want to get yourself something to drink, or perhaps a healthy snack, first. Like maybe a grapefruit? Grapefruit is pretty cool, you know.

Got it? Then read on!

Ecclesiology, for the unaware, is a word for the structure of a Church or other religious body. Now, while I'm sure you've all been hoping for an exciting examination of the structure of 1st century Persian Manicheanism in comparison to the Manichean church of the 4th century, I will instead (surprise!) be examining the ecclesiology of a more obscure religion called...(now where did I put that slip of paper?)...

ahem..."Christianity." Perhaps you've heard of it?

Apparently, Christianity is a pretty big deal. Who knew?

I've been thinking about this topic quite a lot lately, and I have thought of it quite a lot more over the course of my lifetime; this post is essentially me trying to work out and fit together the various thoughts and ideas I've had on this topic in a way that halfway makes sense. It will be mostly speculation, and, while I will make references to sources where appropriate, this is not a real work of scholarship with citations and such--that, if it comes, will be another project. What this is is essentially what I've come to think and speculate after reading many of these sources and trying my best to understand and synthesize them.

Now, the Great Question of 1st century Christian ecclesiology, whether you're a Protestant, a Catholic, or a Whatever, is, essentially, "How do we get from Paul to Ignatius?"

St. Paul thinks

That is, the Apostle Paul's writings (which you can find in the New Testament) are pretty much THE source we have as to the day-to-day workings of the various Christian churches circa 50-60 AD, and from them, people have developed all kinds of theories about how things worked; these are supplemented by information we get from the Didache (a 1st century catechitical text) and the other books of the New Testament. While I'll go over it in more detail later, the long and the short of it is that the Pauline letters show us a church structure with basically two levels of organization: the local one, composed of officials known indifferently as "presbyters" (elders) and "episkopoi" (overseers) and inferior officials known as deacons; and the super-local one, composed of inferior officials known as "prophets" and "teachers," and superior officials known as "Apostles."

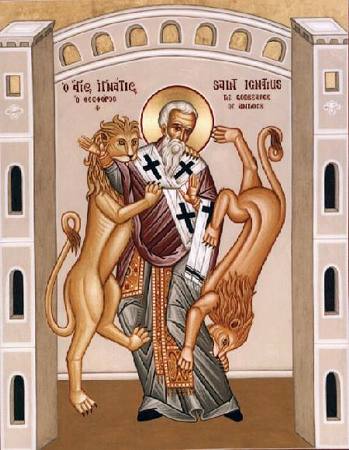

St. Ignatius plays with lions

However, if we jump about 50 years forward to the years at the very beginning of the 2nd century, shortly after the death of the last Apostle, we have seemingly a completely changed ecclesiastical structure, universal throughout the entire Church. One of our earliest and best sources for the structure of the Church at this time is St. Ignatius of Antioch, a Bishop (hey, what's that? you may ask. Well, that's kinda the point) of Antioch in Asia Minor, who at around the turn of the century was forcibly removed from his flock and taken to Rome to be fed to the lions. Along the way to his destination, Ignatius wrote a series of letters to various prominent churches in the Roman world, presenting his final lessons on doctrine and practice while preparing to meet his Lord. In this letter, Ignatius emphasizes one single thing over and over and over and over again, with as much emphasis as it is possible to give anything: the absolute centrality and necessity of communion with "the Bishop," the singular official presiding over almost every Church throughout the world. The Bishop, Ignatius makes clear, is simply the fulcrum point on which the Church itself hangs; those who are in communion with the Bishop and obey his authority are within the visible bounds of the universal Church, and those who are not are heretics and schismatics. And lest you think that this was simply Ignatius day-dreaming a little bit on the road, his letters (and the fact that they were preserved by the communities he sent them to) make it very clear that all the Churches he writes to

already possessed just such a Bishop, who already made all these claims and was obeyed by the vast majority of the faithful. Besides this, in every place to which Ignatius writes, there are also the two other groups of officials which we have already encountered, the presbyters and the deacons, whose role (according to Ignatius) is to assist the Bishop in carrying out the work of the Gospel. Apostles, as we might expect, are looked back on as part of a past age.

So, looking at this development, one question should jump out at us almost immediately: Whence the Bishop? Where did this Bishop guy come from, anyway, and why is he suddenly the boss? Over the course of the years, scholars, theologians, and people in tutus have proposed any number of theories as to the origin of what is called the "monarchical episcopate" (or, put more simply, the Bishop being in charge), the most prominent of which are probably the theories of Apostolic Succession and Gradual Elevation. The first theory is that the Bishops were appointed by the Apostles as their direct successors, to, essentially, fulfill their role in the community; the second is that the role of the Bishop developed gradually over time from within the ranks of the presbyterate, with one presbyter gradually becoming more and more prominent within the body until he came to be seen as an order existing above it. We'll go over what I think of all this a bit later.

However, this is not the only major question of first-century ecclesiology. Even if we leave aside the seemingly post-Biblical role of the Bishop, there's still the question of what, exactly, is meant by the terms presbyter, episkopos, apostolos, and diakonos, officials whose roles are all very much debated in scholarly and Christian circles. This question is obviously one of great importance, as it has important implications for how we view the entire question of ministerial roles in Christianity, the priesthood of all believers, apostolic succession, etc.